Producing theatres

Royal Exchange Theatre

Joint Artistic Directors Roy Alexander Weise and Bryony Shanahan announced that they would leave in September after less than four years in the post, and for a year of this, the theatre was closed due to COVID—in fact, the first productions programmed by them for the main stage didn’t open until June 2021.

On top of that, the theatre announced it would not be replacing them, and that instead of an Artistic Director, they will recruit a trio of ‘artistic leaders’ led by a creative director who would not actually create or direct any work for the stage but would be responsible for “devising strategies and programmes of work that respond to our audience and contemporary challenges”. Cutting through the corporate-speak, this does sound like creating safe work that gives the audience what they already know they like rather than taking any creative risks that may actually challenge or provoke audiences, but I could be wrong.

The new season recently announced includes two twentieth century British classics that have been performed before on this stage within the last twenty years, a Pulitzer Prize-winning American play and a Bruntwood Prize-winner, finally getting its première production five years after receiving the award.

The Exchange kicked off the year strongly with Beginning, the first play in David Eldridge’s trilogy of modern relationship plays that made me hope that the sequel, Middle, would soon make its way to Manchester—and that he’d finish the third play, the title of which we could probably guess. This short, interval-less play was followed by a considerably longer but pretty compelling production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams.

The broad humour of the Exchange’s production of No Pay? No Way?, adapted from Dario Fo, for me lost its way as a satire and its pace as a farce and felt a lot longer than it needed to be. Kimber Lee’s Bruntwood International Prize-winning untitled f*ck m*ss s**gon play, on the other hand, used humour and an unusual plot structure to make some strong points about the representation of East Asian people and culture on Western stages—Mei Mac, who played the lead, spoke to me about it for the BTG podcast.

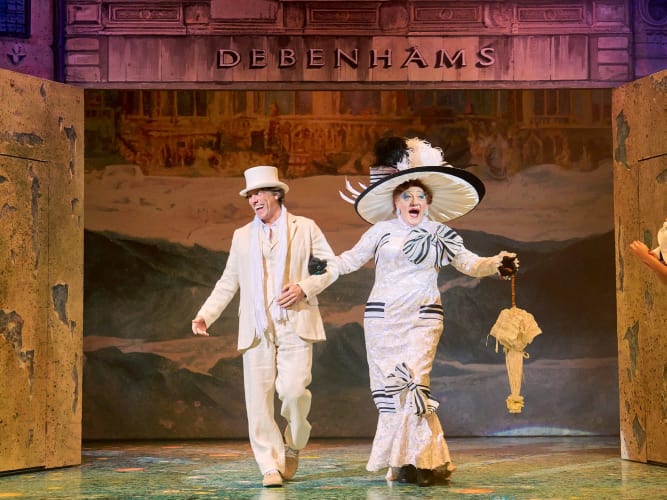

Also for the podcast, I interviewed Pooja Ghai, director of Tanaka Gupta’s adaptation of Dickens’s Great Expectations relocated to Bengal during the Indian partition, which worked surprisingly well—extremely well, in fact. A modern Manchester setting for Romeo & Juliet with the young characters as stereotypical ‘Mancs’ had some interesting ideas but overall I found it to be a bit flat and ‘style over substance’. The year ended with the latest in a proliferation of productions around the UK of Emma Rice’s adaptation of Noël Coward’s Brief Encounter, which had some good performances but was rather too slow and ponderous for me.

Contact

Manchester’s theatre for young people, Contact, reopened in late 2021 after a much-delayed refurbishment had kept it dark for almost four years. The following year, Keisha Thompson was appointed as the theatre’s first female, first Mancunian and youngest Artistic Director and CEO. She spoke to me for the BTG podcast about her plans and about how this had been her dream job since joining the youth theatre group at Contact when she was 15.

Just before Christmas, Contact announced that it was following the Royal Exchange in scrapping the role of Artistic Director. Keisha would instead work one day per week for a commercial company owned by Contact dealing with hire and consultancy. The theatre’s statement that there would be "reduced programming from spring 2024 and an increased focus on commercial activity" appears to point towards it turning into at best a small-scale receiving house and at worst simply a space for hire, but we’ll have to wait and see.

I only visited Contact once in 2023 as it is mostly covered by David Cunningham, but I did see Keisha’s own play 14%, which made some very interesting if not entirely successful use of different playing spaces and split audiences on simultaneous timelines. Her new play The Bell Curves will be produced at Contact before the theatre, to use her own word, ‘pivots’.

Octagon

I’m sure the Octagon is feeling the pinch as much as anyone in the arts at the moment—they wave collecting buckets and contactless payment machines at exiting audiences after every show—but under the effective leadership of Chief Executive Roddy Gauld and—soon to be Greater Manchester’s last Artistic Director standing at a major producing theatre—Lotte Wakeham, they are continuing to do successfully what many other theatres have been cutting back on: producing shows. Part of their strategy seems to be to partner with other theatres on co-productions, which they did for most of their output in 2023 and are doing for many of the shows so far announced for 2024. This way, they can share the costs with other producers without skimping on budgets and quality.

At the start of the year, The Stage Awards recognised Jim Whaite, who has just celebrated 50 years working at the Octagon, with an Unsung Hero Award, and the theatre itself was nominated for Theatre of the Year.

It opened the year with a play by a man often said to be Bolton’s most successful playwright as he grew up in the town, although he was born in Ireland and spent most of his life living elsewhere. Spring and Port Wine has been produced several times before by the Octagon; this production had some good performances but did nothing to change my view that Naughton’s plays tended to be overly long and wordy, which is rarely good for a comedy.

I’ve never really understood the appeal of Amanda Whittington’s plays, other than for amateur groups looking for light comedies with largely female casts (not all of my BTG colleagues agree), but this co-production of Ladies’ Day, with some updating from the playwright, worked better than any others I’ve seen and was quite entertaining.

The Time Machine: A Comedy was the first of three productions at the Octagon this year that fell into that now-common style of taking an old novel and creating a fast and furious comedy from trying to stage it with a very small cast. However, while this started looking like other shows of this type, it turned much darker and more interesting later on. Original Theatre is still touring this production, and it is available to watch online until 2025.

The Book of Will was the remarkable story of how some of Shakespeare’s friends and colleagues came together after his death to compile the First Folio, without which many of his most famous plays could have been lost forever. While not the greatest of plays, its story is fascinating and important, especially in this 400th anniversary year of the Folio’s publication.

It doesn’t seem that long since David Thacker was directing some arguably definitive productions of Arthur Miller’s plays, but this powerful co-production of A View from the Bridge was a worthwhile revisiting of this play and the highlight of the Octagon’s year.

Back to the novel adaptations, Jeeves & Wooster in Perfect Nonsense had some brilliantly imaginative touches and largely preserved Wodehouse’s unique style of wit, and Around the World in 80 Days had some interesting ideas for taking a slightly tangential approach to adapting the book that didn’t entirely come off, but there was much to enjoy. There was a special treat for audiences of the latter show just before Christmas as Artistic Director Lotte Wakeham made her on-stage debut at the Octagon for three performances in several roles when three of the cast fell ill.

Hope Mill

I’ve often said that I don’t know how Hope Mill manages to make the numbers add up for its large-scale productions of musicals with live musicians in its tiny venue, but that is just what it has been doing since 2015, with some shows going on to tour or to West End theatres. However, they announced this year that they are struggling to put on the shows they want and be financially viable, so they are looking at opening some shows in other nearby venues. The first of these to be announced is a musical of A Christmas Carol with music by Alan Menken, lyrics by Lynn Ahrens and book by Mike Ockrent and Lynn Ahrens at The Lowry in Salford for Christmas 2024.

But for 2023, they continued to rediscover musicals that we are unlikely to have seen before, starting the year with Head Over Heels: The Go-Go's Musical and ending it with To Wong Foo: The Musical. While neither can be said to be lost classics, they were both fun shows produced to Hope Mill’s usual high standard.

Aviva Studios

After delays and massive increases in the budget, Factory International, the company behind the biennial Manchester International Festival, finally opened its new venue on the banks of the River Irwell, which may not be entirely as it was envisaged originally but is still an impressive building. But after years of being told of the importance of the Factory name because of Manchester’s industrial heritage, Factory Records etc, naming rights were sold at the eleventh hour to a London-based insurance company to make up a shortfall in the budget, so it was opened as Aviva Studios. Perhaps it will revert to something more relevant to the city when the contract runs out.

The opening production, Free Your Mind, was quite a statement, with a production team to rival that of a Hollywood movie and a world-famous film director, Danny Boyle, at the helm. Based on the film The Matrix, it utilised both of the huge performance spaces in the venue for a dance-drama that wasn’t always comprehensible, even if you knew the original movie (less so if you didn’t), but it was certainly a stunning spectacle that announced the Studios’ arrival.

There was a dearth of theatre for children in Manchester over the festive period, but Aviva Studios came up trumps for these poorly served theatregoers with a large-scale production on the main stage of a new adaptation of Lost and Found, based on the children’s picture book by the wonderful Oliver Jeffers, with songs by Gruff Rhys. It wasn’t perfect, but it’s great to see a theatre such as this one investing as much in theatre for young children—traditionally underfunded and often, unfairly, less well regarded—as for any of its major festival pieces.

Oldham Coliseum

Towards the end of 2022, Artistic Director Chris Lawson was appointed Chief Executive to replace Susan Wildman, who left “by mutual consent”; Jan O’Connor stepped down as chair of the board of directors at the same time. This followed the announcement that the theatre was to be removed from Arts Council England’s NPO list from the following April, thereby losing a major source of revenue funding.

This was seen at the time as making a mockery of the government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda that saw London-based organisations such as English National Opera also being struck from the list following pressure from one of many recent and short-lived Culture Secretaries (so much for the arms-length principle…). Unlike some of the other victims of this round of funding announcements, the Coliseum is in an area defined by ACE as one that has historically suffered from low levels of funding. By February, it was confirmed that the theatre would close for good at the end of March, but it did so with a single performance of a star-studded ‘greatest hits’ show, the tickets for which sold out in half an hour (I didn’t get one).

A report commissioned by the new Coliseum board indicated that ACE’s withdrawal of funding wasn’t as sudden as it seemed to outsiders, as concerns had been raised before about the management of the organisation and reforms to the board of trustees were apparently not adequate to address these. However, fans of the theatre have refused to accept that it is not viable to reopen the existing building and have claimed that the facilities in the building which is to replace the Coliseum, which has yet to be built, are completely inadequate.

Chris Lawson, after a time as Director of Producing and Programming at the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh, will take over as Chief Executive at The Dukes in Lancaster from January 2024.

Royal Court

I’ve long admired the Royal Court’s support of local writers writing specifically for a popular Liverpool audience, but I’d not actually seen anything there until this year, when I decided I had to go to see the stage première of the 1980s TV series Boys from the Blackstuff. I had the original writer, Alan Bleasdale, sat behind me and the adapter, James Graham, in front in a packed Liverpool audience as finely tuned into the politics as the domestic turmoil of a powerful drama that had a massive impact across the UK in the 1980s and still resonates and feels relevant and necessary forty years on.

I returned to the Royal Court for my first panto of the year, an adult show titled The Scouse Dick Whittington, for which they’d managed to recruit the co-writer and director of a great many past rock ’n’ roll pantos at the Liverpool Everyman, Mark Chatterton, as director of Kevin Fearon’s script. It was perfectly tailored to this theatre’s regular audiences, and I even had my first Christmas dinner served to me at my seat in the theatre before the show.